At the end of the day of the pig roast, on a Sunday in mid-October, a few of the last remaining folks settled by the bonfire with glasses of whiskey, a few loaves of fresh bread brought from the city, and a brick of butter we’d pressed down the street. Four cooks from a restaurant in Manhattan had just arrived, after most of the guests had left, and they seemed happy enough to sit outdoors by the fire for an hour or two, before hitting the road again in the dark. One of the restaurant boys said he was thinking about working on a farm. He was twenty-two years old, and figured if he wanted to try farming, he didn’t want to waste the time in his life when he could do it. He was curious what it was like to work at Eckerton Hill.

I felt like a first-year girl talking to a prospective student. I told him I had no regrets about coming to work at Eckerton. I told him why this farm had made sense for me in the beginning: I didn’t have a car or a license, but I had a friend on the farm who would teach me to drive, and who would share the use of his car. I hadn’t wanted to leave the Union Square scene behind altogether. It would be easy to visit New York, and easy for friends from the city to visit. I knew I would be proud to sell Tim’s tomatoes, and I was interested to see how restaurants placed their orders, how Tim and Wayne decided what to sell wholesale and retail, what went to distributors or restaurants, and how much was sold on the stand. I knew Tim would pay a reasonable wage. And I was attracted to the dynamic between the people who sold at the market, when I shopped there for The Spotted Pig and The Breslin. Our conversations every market morning made me wish I worked with them.

Trying to explain now why Eckerton Hill may or may not be a good place for someone else to work was more difficult. I can trust describing what it has been like for me, what it was like this year, with these people, and this weather, at this time in my life. Everything could be different next time around. This year there was very little rain, record heat, the most tomatoes ever, and three people in the farmhouse who did things together. There was too much dishwashing, a solid dose of drinking, not enough writing, and not very much time by myself. The walls in the house are thin, and the refrigerator is always packed to the gills and dripping with pickled jalapeno juice, meat jizz, and moldy lemons. The sink in the bathroom is basically caked with soil sometimes, Tim spends time writing and brooding in the living room, and occasionally shouts out to us in our beds on Sunday morning. Nothing is open in town on Sundays except the 24-hour major grocery store. Sometimes everybody we know in town seems like a stoner, and sometimes I drive away from the house just to drive. I couldn’t stand picking summer squash, I wish we sold produce to the local community, and I’m helplessly annoyed that we don’t have a good way to sell greens at the market without them wilting in the sun. The fly strips in the house are disgusting. The freezer releases an avalanche every time it’s opened.

But by now I say all of this fondly.

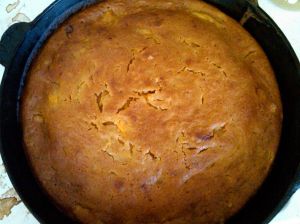

The spring was predictably novel, an exhilarating break from the city. And the summer felt like one blazing rush of adrenaline. But arriving at the fall has made me want to stay. It is the best of progressions: from the cold water washing lettuces in the spring, to the sweaty circus act of the summer, to the relaxed remnants of work in fall’s flannel plaid shirts, with a view of the muted or bright colors of the trees and hills. Now we stop and smell fallen leaves and stacked up wood, where once we knew only humidity, heat and the sweet smell of rotting tomatoes. The wind blows off our hats that two months ago kept our necks from burning. The warmth of the goat at my side is welcome in the chilly near-frost mornings, so much so that it’s hard to remember feeling the sweat start to drip down my neck, milking at five am in July. We wake up later now. Caroline has joined us. We are cooking dinners again. Roasted sweet potatoes and sautéed brussel sprouts with bacon, curried goat with scotch bonnets, kale salads with aged cheddar, grilled fish with aji limon peppers, pasta with chard and sprouts, sweet potato hash with bacon in the morning, lentils with aji dulce peppers, turkey chili with habañeros, three bean soup with grenadas. Goat’s milk makes for a mean hot chocolate, and the walk-in is stacked with gallons of cider. The work is light, the crew is smaller, Tim is more relaxed. And we are starting to have lives again, to talk about shows in Philadelphia, gallery openings in Bethlehem, and museums we’d like to visit. I don’t fall asleep every time I start reading. It seems that this farm is a wonderful place to live and work. So I continued to try to explain.

You do not learn how to farm in a year. And you may not learn much at all working for a decent wage, on land that is cultivated for a profit and not for education. I never strung the tomatoes because other people were faster, I rode the tractor once just to drive it, from the field to the shed, and I never managed the restaurant orders. I wasn’t here when we seeded most of the tomatoes, and the craze of irrigation this near-drought summer taught me primarily that water is a stress-inducing element. We only made three kinds of cheese all summer, and I do not know if the goats were happy in their fenced-off space. I don’t know what blight looks like because we never got it, and I still couldn’t tell you many of the names of our tomatoes and peppers.

I learned some things. I learned that I do like to work outside full-time, that sunny days are worth the rainy ones. I learned that I like feeling physically exhausted from productive work every night, rather than running in the same circle every morning; that I can work in humid heat; that I can pick tomatoes for a twelve-hour stretch without feeling miserable at all; that I can live in a small town and not go crazy for the city; that I can play pool and drink Yuenglings in a fluorescent-lit basement bar in Kutztown and not yearn for the backyard, speakeasy styles of Brooklyn. I learned that I can be a passenger on the ride into the city at 3:30am, work the market all day, stay awake for the ride home, and still have energy that night. I learned that I can work and live with a bunch of boys and still love them. I learned to drive. I learned what this lifestyle is like – the life of a farmhand at this particular farm – and it made me want to do it again, to try a different one, to perpetuate the way I have felt here instead of the way I felt working in the city.

So I will continue to farm for now. In Vermont this next season, on a very different farm, in a very different climate, for different reasons than the reasons I came here. And I guess I think if any farm can lead someone to do that, if any farm can teach a young person to think about farming more, even farming for themselves, then for sure, it is worth working there. Find your own place, for your own reasons. But the next generation of farmers has to put boots on somewhere.

You must be logged in to post a comment.